Those who foresee promising prospects for India always emphasise the demographic dividend that the country has been reaping in the past 10 years in a trend that is expected to continue well into the middle of the century. An aspect that is often neglected in this narrative is the alarmingly high level of malnourishment among children and distressed levels of educational outcomes among young adults, particularly in rural India.

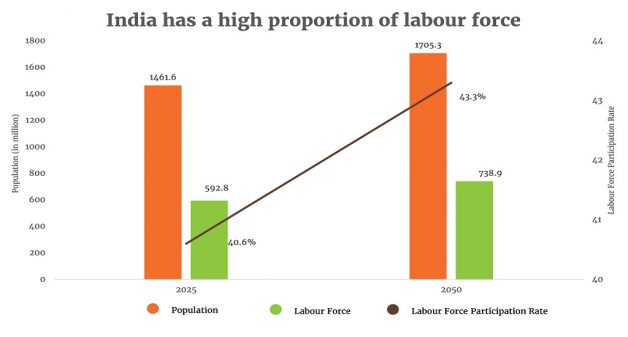

A significant percentage of the population of India is young, and will remain so at least till 2050. About 10 years from now, 593 million Indians will be participating in the work force, which is as much as 54.2% of the total population, according to projections by the International Labour Organisation. India is poised to become the world’s youngest country by 2020, with an average age of 29 years. It will account for around 28% of the world’s workforce by 2020.

This is the crux of India’s demographic dividend, which is the economic growth potential when the share of working-age population (15 to 64) in a country is larger than people who are 14 and younger and 65 and older, according to the United Nations Population Fund.

In order for this economic growth to occur, the younger population must have access to high-quality education and adequate nutrition. In other words, India can benefit from a young population only if they are healthy and well trained. For this to happen, Indian children, particularly in the rural areas where the majority of the population resides, must grow up to their full potential.

India’s poor food, health and education delivery systems may severely crimp this potential. It is evident that malnutrition in the early years severely affects cognitive abilities in children. Data collected over the years seem to bear out the correlation.

Underdeveloped children

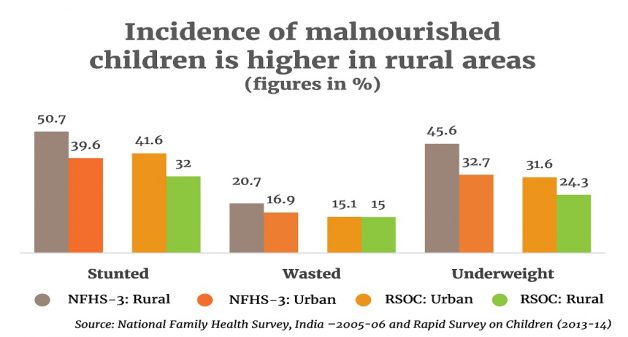

For instance, India had a population of around 129 million children who were under 5 years of age in 2006, according to United Nations estimates. As much as 48% of them were stunted nationally, according to the 2005-06 National Family Health Survey. As with any other major social indicator, the situation was particularly bad in rural India. A majority (51%) of children till 5 years of age were stunted in villages compared with 40% in urban areas.

Stunting is a widely used measure of nutritional status among children. It is defined as the percentage of children (0 to 5 year) whose height for age is below minus two or three standard deviations from the median of child growth standards of the World Health Organisation. Stunting is a sign of chronic under-nutrition. It is responsible for nearly half of all child deaths globally.

Link with education

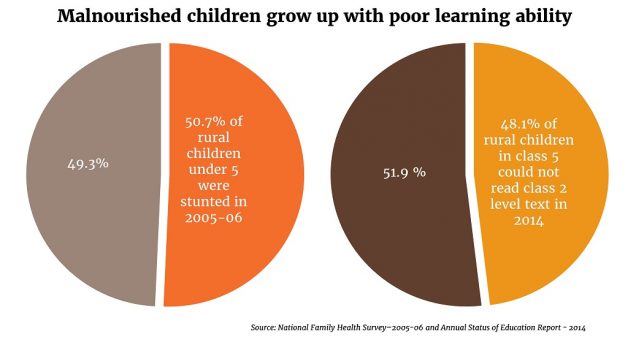

A look at the educational outcomes numbers eight years later and matching it with data on stunting is revealing. In 2014, when most of the children in 2006 would have been studying in Class 5, 48% of them in rural areas failed to read texts meant for class 2, according to the Annual Status of Education Report by Pratham, a non-profit organization.

It seems clear that stunting leads to an underdeveloped brain, diminished mental ability and poor school performance in children. This is sure to translate into reduced earnings and increased risk of chronic diseases when these children grow up into adults.

It is alarming that despite economic growth, India is unable to reduce the level of child malnutrition. The Rapid Survey on Children conducted in 2014 found that 42% of the children in rural areas and 32% of urban children who were under 5 year of age were stunted.

The Global Hunger Index report released by US-based International Food Policy Research Institute on Tuesday, October 12, showed that 38.7% of under-five children in the country were stunted. In the 2016 rankings of 118 countries, India is ranked 97, compared with China’s 29 and Pakistan’s 107. All other Asian peers are doing better.

The trend in educational outcomes is equally dismal. Reading levels declined from 52.8% in 2009 to 48.1 % in 2014 in rural areas, the ASER reports show. The ability of class 5 students to perform simple division fell sharply from 38.1% in 2009 to 26.1% in 2014, the latest year for which ASER data is available.

Unpromising future

Now imagine the situation about 10 years from now. In 2025, as much as 40.6% of India’s population will participate in the work force. Of those 593 million people, a majority will be from the rural areas. By the middle of this century, the labour force participation as a proportion of the population will rise to 43.3% and the number will climb to 739 million.

Most of them, if past data trends hold true in the near future as well, would have been stunted as children and performed poorly in school as young adults. How would they perform when they start their productive lives? How would they compete in an increasingly tough world and be able to improve their lot? Would they be the demographic dividend that the country had anticipated?

Soumya Sarkar is Editor of Village Square. Follow him on Twitter @scurve.