Groundnut farmers get a protective shell in Andhra

Coming together as a collective, groundnut farmers of Andhra Pradesh earn the rightful income for their produce, reduce risks and develop multiple income streams.

Coming together as a collective, groundnut farmers of Andhra Pradesh earn the rightful income for their produce, reduce risks and develop multiple income streams.

Ananthapuramu district of Andhra Pradesh has historically been the largest producer of groundnut in terms of area under cultivation and production. But much to the dismay of groundnut farmers, a formal market for selling the produce was nearly absent in the district prior to 2005.

The produce was sold to traders from Kurnool, Challikere, Ballari and other nearby areas in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. Farmers had to accept random weighing stones brought by traders and any price the trader deemed fit. There was no concept of quality, standardised weights, storage and processing.

The farmer was forced to sell the produce at any meagre price the trader offered due to lack of awareness and immediate requirement of cash after investing every penny for four long months. Instances wherein a trader procured all the produce after promising to pay the farmer later but never turned up again, were not rare.

The situation has changed now, with the formation of farmer cooperatives bringing better profits for the groundnut growers.

In 2005, five farmer cooperatives (sangha) were formed in the Penukonda mandal of Anantapur – as the district was known then – with the support of Centre for Collective Development (CCD). Immediately after coming together, the farmers were trained in using standard weighing equipment, importance of outturn percentage and moisture content in groundnut.

A bag of 42 kg was sold at Rs 1,000 by pooling the produce of all the five sanghas’ farmers while the market price then was Rs 1,010 per bag.

“If the produce was sold to a trader, the trader took at least 4 kg per bag additionally, cheating the farmers,” said Ashwat Narayana, former president of the federation.

Later, farmers pooled money and bought 2.5 acres land for establishing a mill. National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) supported the cooperatives to access a loan and build the mill.

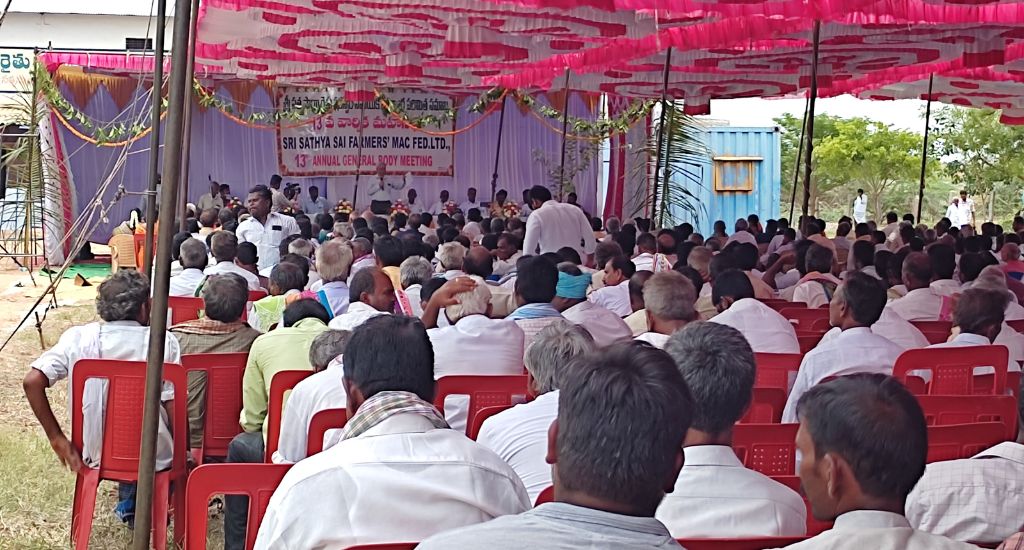

In 2009-10, Sri Satya Sai Raithu Mutually Aided Cooperative Federation (SSSMACF) Ltd was registered. The cooperative collects a membership fee of Rs 100 and share capital of Rs 200.

Also Read: Sinnar farmers switch to multi-cropping for resilient earnings

The cooperative collects a range of price quotes and groundnut requirement from the market including corporate entities. The farmers then receive an average procurement price estimate via a mobile text message. The prices are based on the quality of the groundnut. But the produce is never rejected if a farmer wants to sell to the cooperative.

The groundnut is procured at the farm gate and within eight days the amount is transferred to the farmer’s account.

For every bag of groundnut sold by members through the cooperative, Rs 100 is withheld and added as deposit in each member’s name. This total deposit is used every year for the working capital. The farmer receives interest at the rate decided by the scheduled banks on their savings deposit after every five years.

The major challenges that producer cooperatives in India face are member loyalty to realise economies of scale, finding the market and price volatility. SSSMACF manages such risks in a carefully calculated manner.

The federation informs members of the on-hand price they will receive after subtracting the cost of procurement, processing, grading, transportation, GST for value added products and any other administrative expenses.

The average price at which the retailers or corporate companies buy the groundnut has certain terms and conditions associated with it. The purchase orders are carefully read and requirements are communicated to the members.

Farmers are not pitted against the vagaries of the market but assured of appropriate prices.

“The idea of local consumption and localised economy without estimating the production-to-demand ratio is preposterous,” said Trilochan Sastry, the founder of CCD. “Why should farmers take on the responsibility of automatically translating production into equal demand for that commodity in the same region? There is a need to plug the gaps in production capacity and consumption demands while ensuring best possible prices for farmers which is where collectives play an important role.”

Also Read: Water control is the strongest anti-poverty measure

There is no binding on the members to sell the produce to the cooperative. Also, non-members can sell the produce as well, following the quality norms. If the farmers receive a better price and feel assured about receiving accurate prices, they are free to sell in the open market.

“In the interest of the collective, we don’t want to compromise on individual profits. We see demand arising out of anywhere. Despite that, we have never experienced huge losses,” said Shankar, the project manager at SSSMACF.

Four years ago the CCD also started Farmveda for farmers to market through their own brand of value-added products like groundnut oil, protein bars, groundnut chutney powder and peanut butter.

Another initiative started by the federation was making organic fertilisers such as phosphate and potash by procuring organic waste from farmers. A bag of potash costs Rs 1,050 while phosphate is sold at Rs 1,400 in the market. The federation supplies them to the farmers at Rs 700 and Rs 720, respectively, without charging for transportation.

The other sources of income are community-managed seed systems and the government’s procurement at minimum support price (MSP). The federation supplies input seed for farmers at MSP and receives 1 percent as service charge from the total cost of seed supplied to other farmers from the government.

Recently they tied up with IITians for Influencing India’s Transformation (IIT-IIT) to map local ponds and tanks. The cooperative supports the desilting work and supplies the silt as a fertiliser. This increases the water holding and absorption capacity of the water bodies.

Currently the cooperative has 26,527 farmer members in around 400 villages spread across 37 mandals of Ananthapuramu and Satya Sai districts. The cooperative is self-sustainable with no external funding. In the last 13 years, the federation has conducted business worth over Rs 180 crore.

Also Read: How a tribal women-run magazine changes life for the better

For cooperatives to become successful, values such as trust, solidarity and democracy alone do not suffice. A strong business plan with economic profitability at its core is essential, as proven by this groundnut farmers’ cooperative.

The lead image at the top shows a farmer holding groundnuts. (Photo from Shutterstock)

Sameera Kasulanati is a researcher at VikasAnvesh Foundation, Pune.