Dwindling snowfall leading to water crisis in Ladakh

As valleys in Ladakh rely on snowfall and glaciers for their water needs, unpredictable weather changes are leading to water scarcity, severely affecting the livelihood of villagers.

As valleys in Ladakh rely on snowfall and glaciers for their water needs, unpredictable weather changes are leading to water scarcity, severely affecting the livelihood of villagers.

It’s getting warmer and drier in the country’s cold desert. Known as the place where mercury drops several notches below zero and mountains remain barren through the year, Ladakh, well, is changing. From Zanskar to Nubra, a significant number of villages in the Himalayan region of Ladakh are facing water crisis. Reduced snowfall has begun causing issues for people, agriculture and livestock.

Ladakh’s climate is arid and cold, with low annual precipitation. The region relies primarily on snowmelt and glacier runoff for its water supply. But now variability in snowfall and increasing temperature due to climate change are reducing the amount of available water.

“Ladakh has seen major uncertainties in annual snowfall and rainfall in the last decade. Never have we seen such erratic climate conditions – less snowfall and heavy rainfall,” said Sonam Lotus, the director of Indian Meteorological Department, Srinagar.

Also Read: Artificial glaciers help mitigating rural water crisis in Ladakh

Glaciers in the Himalayan region, including Ladakh, are receding due to rising temperatures. This reduces the flow of glacial meltwater into rivers, affecting water availability downstream.

The water crisis in Ladakh is leading people to migrate out of their native villages. For instance, Kulum village bears a desolate look now. The inhabitants have completely abandoned upper Kulum and moved towards a neighbouring village to seek alternative livelihoods.

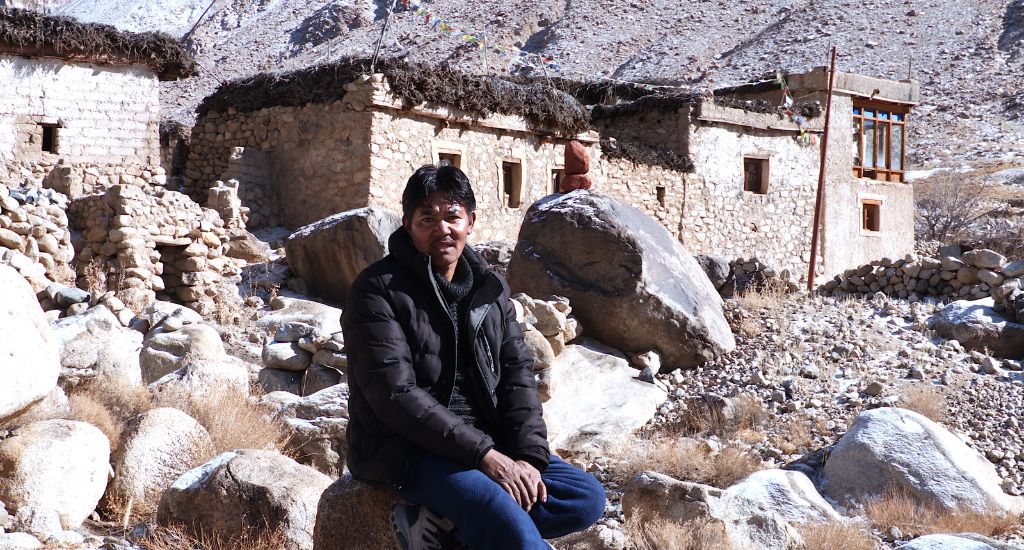

Kunsang Norbu, 40, was born and brought up in Kulum village, which lies surrounded by mountains and wildlife 50 km southeast of Leh.

“In a span of four decades, I have already seen two lives,” he told Village Square. “I experienced a happy childhood with thriving crops growing in fields and healthy livestock, all managed by local traditional systems. But in my present life, I see entire agricultural and traditional practices falling apart.”

Norbu now works as a daily wage earner in Leh, where he longs for home and often feels nostalgic, filled with the desire to return.

Also Read: Ladakh’s Chipko: Mothers out on streets to save ‘sacred’ juniper trees

“The painful uprooting from my native land is not even my fault. Yet I have to pay the biggest price. I hope one day I will go back and plan my son’s wedding in my ancestral home,” said Norbu.

Changes in snowfall patterns and the availability of water can affect crop yields and agricultural practices. Farmers find it increasingly difficult to grow crops or rear livestock. Without the animals, the villagers lose their food supply and clothing.

“Yaks and sheep are integral to our livelihoods. This acute water shortage is forcing us into the sinful act of abandoning them. It’s the last thing I want to do,” said Thukchey Gyatso, 54, of Pishu village in Ladakh.

Chu mat, skitpo mat (no water, no joy) is a phrase that reverberates among the people of Pishu. This village of 29 households is situated above the west bank of Zanskar River in Ladakh. It has found critical fame for severe seasonal water shortages within the Zanskar valley.

Similarly, located in the Siachen belt of Nubra Valley, Ayee, which has 192 villagers, often sees clashes over water. Residents of the quaint village, which is located on the bank of Siachen River, have been dependent on agriculture. But since 2017, they have had to incorporate major changes in their farming activities. Natural springs – which are the traditional water source – have got buried in mud slides. The villagers have to wait for shared irrigation water from Kube, a nearby village, that delays the farming activity by a month or two.

Also Read: Ladakh longs for tourists who give region a miss

“The whole agricultural system would have collapsed had we failed to build a promising icefall as an alternative source of irrigation water,” said Lobsang Thardoth, a 51-year-old farmer. With the help of Ladakh Ecological Development and Environmental Group, the village became the first in Nubra valley to come up with an artificial glacier.

The unpredictability in weather events is giving rise to several causes for concern. Villages allege government negligence and limited intervention in alleviating the situation.

“There is a lack of coordination among the various departments concerned and internal politics makes things worse. There is a need for timely governmental intervention,” said Sonam Wangchuk, superintending engineer, PHE Department, UT Ladakh.

Burgeoning tourism adds to the problem of water scarcity, and explains to a large extent the high pressure on groundwater. Last year Ladakh received around 2.5 lakh tourists in June and July, as per official data. This number is double the population of Ladakh. However, the local residents, caught in a catch-22 situation, are now left to themselves to find the solutions for the water crisis in Ladakh.

Also Read: What’s it like to run on a frozen lake?

The lead image at the top shows a woman carrying a basket full of handwashed clothes from the Zanskar River in Pishu village. (Photo by Dawa Dolma)

Dawa Dolma is a freelance journalist based in Leh. She writes about climate change, communities, and culture of the Himalayas. She was a Rural Media Fellow 2022 at Youth Hub, Village Square.