The notice that proves no one takes dowry in this village

Families sign an anti-dowry pact in Babawayil village and rule violations entail social boycott from the masjid and graveyard. There’s been no violation in 40 years.

Families sign an anti-dowry pact in Babawayil village and rule violations entail social boycott from the masjid and graveyard. There’s been no violation in 40 years.

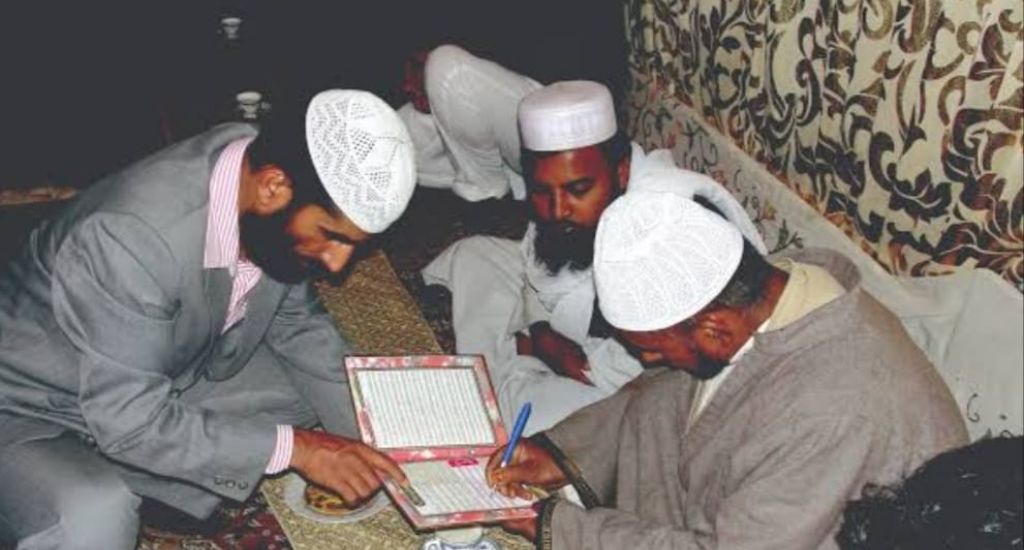

Marriages are made in heaven, but an earthly firman decrees that no wedding happens in a picturesque village of about 6,000 people in central Kashmir without the signing of an undertaking. Kind of like a prenup, the contract is binding on everyone and it says no one will give or accept a dowry — in cash or in kind.

This strict rule, drafted almost four decades ago, has made Babawayil, about 30km north of Srinagar, in Ganderbal district a “dowry-free village”.

“The arrangement has our full backing. Girls are not viewed as a burden or liability in our village. Families no longer need to sell assets to pay for their children’s marriage. Our rules should be followed by all,” said Saima Akhter, a university graduate who got married recently.

Almost all marriages in the village are arranged by family and friends, a long-held custom left untouched by modern views. Dowry was never a bother in traditional Muslim marriages and the only transaction was the “mehr” or bride money paid by the groom during the nikah on a qazi’s watch.

It’s a simple ceremony: “Ijaab” (offer of marriage) from the groom, and the bride says “qabool” thrice. Qabool is the equivalent of “I do”.

Dowry seeped into the system a few decades ago and swelled into a scourge. Marriages became lavish, expenses shot up. The bride’s family was expected to gift — mostly under pressure — expensive jewellery, copperware, furniture, electronics, cars, cash and sometimes well-appointed houses. These were passed over as necessities for a “comfortable head start” to a just-married life.

Also Read | Reverse dowry – empowering or subjugation?

Even the customary wedding feast of Wazwan jumped from a seven-course meal to include more than 30 varieties of food served to guests.

A would-be bride’s father could do little but despair, empty out his savings, sell property or take loans that attracted hefty interests. Skint people had little option, other than letting their daughters sit at home — which again is looked down upon by society and fuels gossip.

Sociologist Ali Mohammad Rather pointed to statistics from a recent survey that says 20,000 young men and women in Srinagar alone have not been able to marry because of the dowry culture and mounting wedding costs.

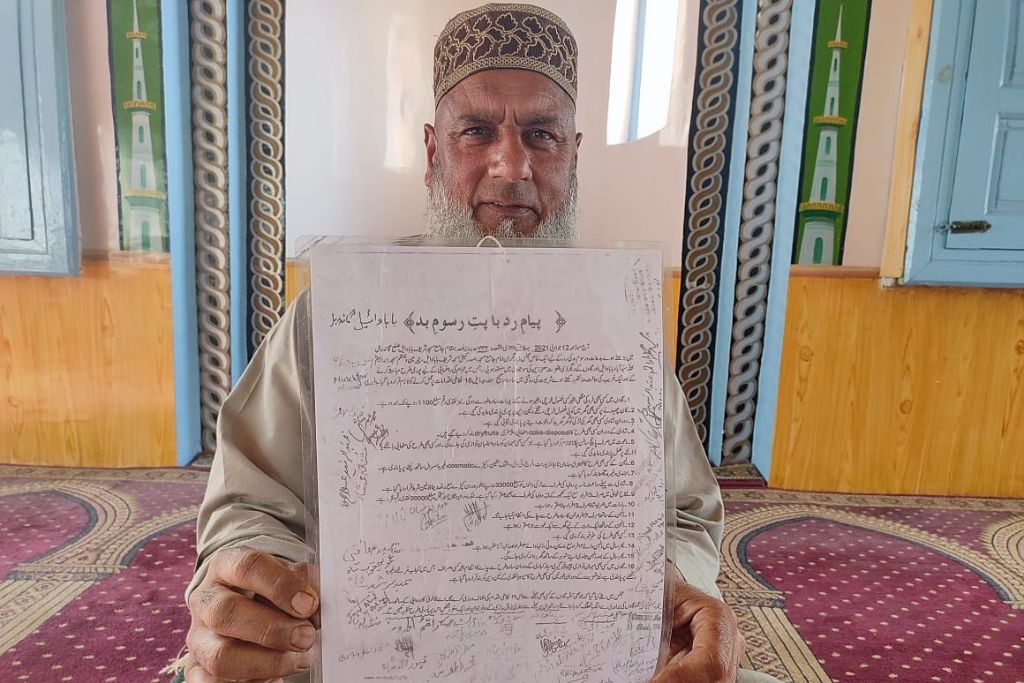

Babawayil resident Ghulam Nabi Shah made up his mind to put an end to dowry and its attendant overheads in the 1980s, spurred by a hard-up relative’s call for help. He and village elders put their heads together and framed the first rules for a simple marriage. The village law debuted in 1985 with signatures from one and all.

According to the initial terms and conditions, the groom was to pay Rs 30,000 as “mehr” to the bride and for expenses like her trousseau. No other transaction of cash or commodities is allowed. The amount was revised some time ago to Rs 50,000 to offset inflationary pressures, said Shah, who is in his late 70s.

The agreement comes with the caveat: break the rule and face social boycott, including a ban on the offending family from the mosque and the graveyard. There has been no violation in four decades.

Babawayil shines out like a guiding beacon in a country where courts are flooded with disputes over dowry payments given by the bride’s family to the groom or his family at the time of wedding.

Dowry was outlawed in 1961 and stronger laws were introduced in the 1980s, but the centuries-old social custom persisted.

Also Read | Salem marriages bane of Malabar girls due to dowry problem

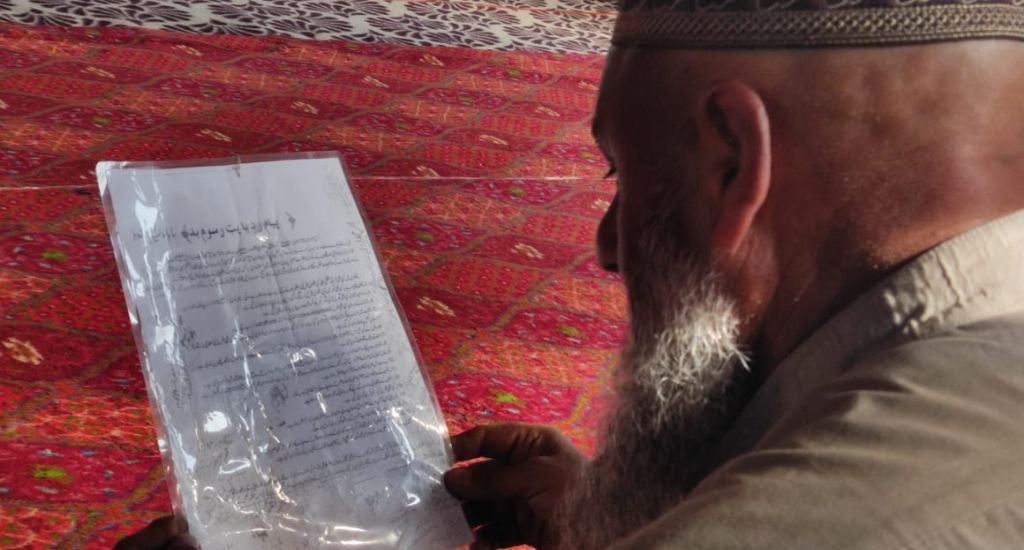

The village’s robust anti-dowry system is opening eyes far and wide. People come seeking guidance or to look at the fine print.

“We are happy to share how this works,” said Shah.

Head cleric Moulvi Bashir Ahmad said: “You won’t find a boy or girl of marriageable age sitting single at home here.”

Marriages are not only a union between two people, but they also serve as a social contract between two families. Parents are convinced that a proper marriage builds a strong family.

“I am a lucky parent to be living here,” said Mohammad Sultan Shah, 57, a father of three daughters.

When a prospective groom’s family came visiting recently to fix the wedding date of one of his daughters, Shah headed straight to the village head to get the papers. They signed the agreement, and the marriage was solemnised after a fortnight.

Shah’s earnings are modest, but he never felt a pinch marrying off his daughter. Thanks to the blanket ban on dowry.

Also Read | ‘We’re good at making laws, not implementing them’

The lead image at the top shows a simple nikah ceremony in Babawayil, a village of about 6,000 people in central Kashmir (Photo by Nasir Yousufi)

Nasir Yousufi is a journalist based at Srinagar.