Coolie number 985 does not find too many goods to carry these days. But instead of lessening the load, it has heightened a burden that Sandeep Singh – a porter at the Attari-Wagah international border crossing between India and Pakistan – is struggling to bear.

Few notice the irony, including the hundreds of tourists who flock from far and wide at the border crossing to witness the high-octane military ceremony staged by both countries every sunset before lowering their national flags.

While the daily spectacle remains loud and boisterous, the actual border crossing between the two neighbours with testy ties has fallen quiet.

Indo-Pak relations hit trade across the border

Once bustling with trucks and goods heading in opposite directions, Attari-Wagah was hit by deteriorating India-Pakistan relations.

Since dozens of Indian security men were killed in Pulwama in the winter of 2019 in a terrorist attack that New Delhi blamed on Islamabad, border trade has dwindled.

India withdrew the status of Most Favoured Nation for trade granted to Pakistan, and imposed a 200% custom duty on its imports. Pakistan too placed curbs on trade following India’s abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir.

The two neighbours were eyeing to ‘punish’ each other with these punitive measures. They definitely have pushed porters such as Singh to penury in the process.

Also Read | Why farmers in this Kerala village pray for peace with Pakistan

Less trade means less trucks and lesser business. It also means little or no work for people such as Singh. Also hit are local traders and dhaba wallahs.

Falling fortunes

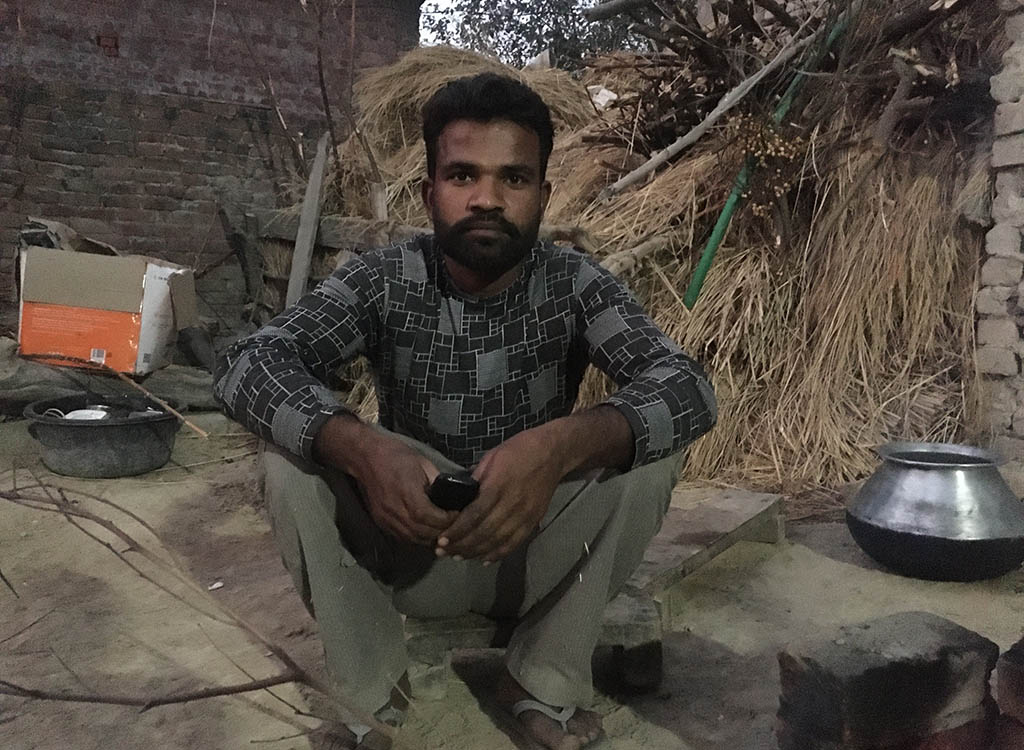

“Life has got infinitely more difficult,” said Singh.

Unable to pay the school fees, Singh and his wife, Rekha, have had to pull their children out of private schools. The children now go to a nearby government school where education is free.

They have also had to sell off family gold. “I sold them since I needed money for my wife’s surgery,” he said. In between, the couple has also had to sell a portion of the ration the family gets under the National Food Security Act. “We sold wheat for Rs 400 to buy medicines for my child when he fell sick,” said Singh.

The downturn in his fortunes has been in step with the declining numbers of the border trade at Attari-Wagah.

Trade down to a trickle

In 2017-18, the overall India-Pakistan trade through the border stood at Rs 6,371 crore. It came down to Rs 2,996 crores in 2019-20. Consequently, the number of trucks arriving at the border came down to 6,655, falling from 48,193 in 2017-18.

The trucks that lined up at the border crossing brought mostly cement, gypsum rock, salt and dry dates from Pakistan. Fresh fruits, vegetables and cotton headed for Pakistan arrived from the Indian side.

But now that the trade is down to a trickle, porters have little to first unload and then load onto trucks for their onward journeys at the crossing.

According to a study ‘Unilateral Decision Bilateral Losses’ by the Bureau of Research on Industry and Economic Fundamentals (BRIEF), 9,354 families have been adversely hit by the curbs on the border trade at Attari-Wagah.

Porters are affected the most

One of the worst-hit are the porters such as Singh. Some 1,433 of them laboured at the bordered crossing. Compared to about Rs 800 they earned daily earlier, they barely make Rs 200 now.

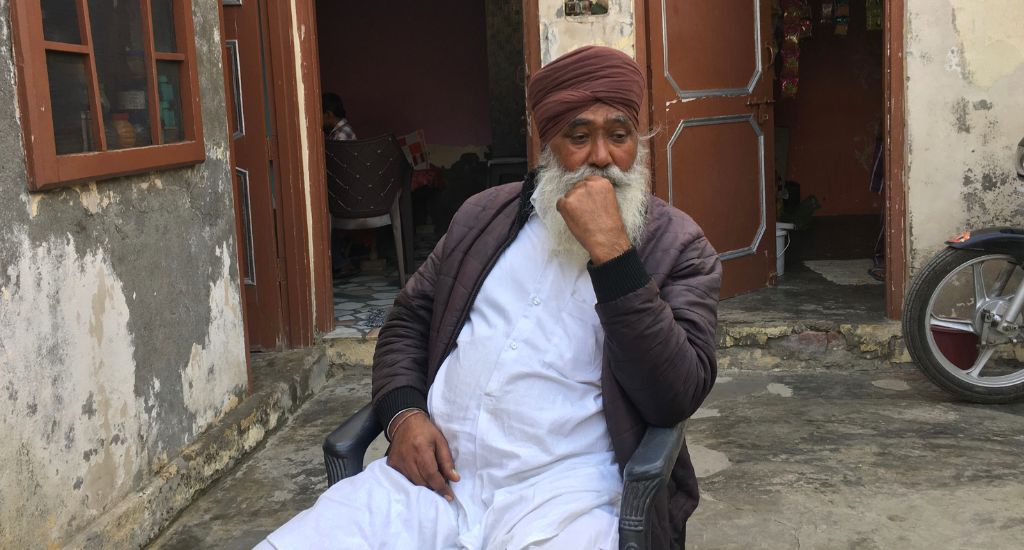

They have been petitioning the Indian government, urging that they be made permanent employees under the Land Ports Authority of India. “The last letter we wrote was in November 2022,” said Ranjeet Singh, president of the Coolie Mazdoor Union.

As they await government intervention, many have turned to odd jobs. Ranjeet Singh now alternates between selling ayurvedic medicines in the nearby villages making Rs 300 a day and working at the border, as and when he finds work.

Sandeep Singh, a Dalit from Attari village, works as a mason.

The stalemate and hard times continue

Hard times bind the porters together living in scattered villages across the region. “Post Kargil too, work had slowed down. Surviving was difficult, but it wasn’t as bad as it now,” pointed out Balwinder Singh.

This time, his youngest son has had to give up his education after completing Class X. He now works as a daily wager to supplement the meagre family income. The family is also slipping into a debt trap, having borrowed Rs 1 lakh from a friend. The interest alone is Rs 2,000 a month.

In the neighbouring Roranwala village, Baljit Singh and his family of five is also struggling to cope with the consequences. They have had to take a loan and have pulled out their two daughters from school.

The mood among the locals is one of overwhelming despair.

“Only the central government can help,” said Malkit Singh, another porter. Though several politicians and political parties in Punjab have called for the resumption of trade at Attari-Wagah, the stalemate continues.

“We see our boats sinking, not sailing,” lamented Sandeep Singh. “There are no factories here and all that we have here is the border. Our lives depend on that,” Malkit Singh reminded.

But then, frosty India-Pakistan ties have stalled the border trade and upended their lives. In the absence of a bilateral détente, the porters are simply collateral damages.

The lead image shows the road at the Attari-Wagah border that is almost empty, because of the trade curb between India and Pakistan (Photo by Sanskriti Talwar)

Sanskriti Talwar is an independent journalist who writes about gender, human rights and sustainability. She is a Rural Media Fellow 2022 at Youth Hub, Village Square.