Arunachal’s Wancho script faces a challenging future

After developing a script for the phonetically nuanced Wancho language of his community, Banwang Losu, a teacher, finds it a challenge to sustain it in the school curriculum.

After developing a script for the phonetically nuanced Wancho language of his community, Banwang Losu, a teacher, finds it a challenge to sustain it in the school curriculum.

Kam means home. The same word means a basket when spoken with a shorter phonetic sound. And it also means the edge of a table when spoken with a high pitch. These words with unique phonetics belong to the Wancho language spoken by the Wancho community in Arunachal Pradesh.

The Wancho community – a Tibeto-Burmese indigenous group with a population of nearly 56,000 – resides in the Patkai hills of Longding district.

While the community has been speaking the Wancho language for generations, it had no script, placing the language under threat.

In 2013, Banwang Losu, who has been working as a teacher for over 20 years, scripted history by creating a new alphabet for the ancient tribal language. But after almost 10 years of the script being developed, Losu faces challenges in garnering support to popularise the script and sustain it in the school curriculum.

Born and raised in the culturally rich landscape of the Himalayan state, Losu, 41, developed a deep connection with his tribal roots from an early age. Recognising the gradual decline of his community’s language and the resulting threat to their cultural identity, he embarked on a mission to revitalise and preserve this linguistic treasure.

Also Read: Learning the ABC of Toto language

Losu learnt about the lack of a Wancho script as a class-11 student when he and his teachers did a study of the socioeconomic conditions of the community. He became so interested and determined that in 2001, he started working on the script using Roman numerals.

“Wancho is a mix of Tibetan and Burmese languages. Initially, I tried to derive a script from Roman numerals and the Devanagari script. However, because of phonetic variations, it was a little difficult to develop a script for this language,” said Losu.

He then started looking at the tones and sounds of the language closely and used symbols and signs specific to the community to develop the script.

The years of research and dedication led Banwang Losu to develop a new script tailored to the unique phonetics and nuances of the ancient language. This newly crafted alphabet captures the essence of Wancho language and provides a contemporary framework for its continued usage and study.

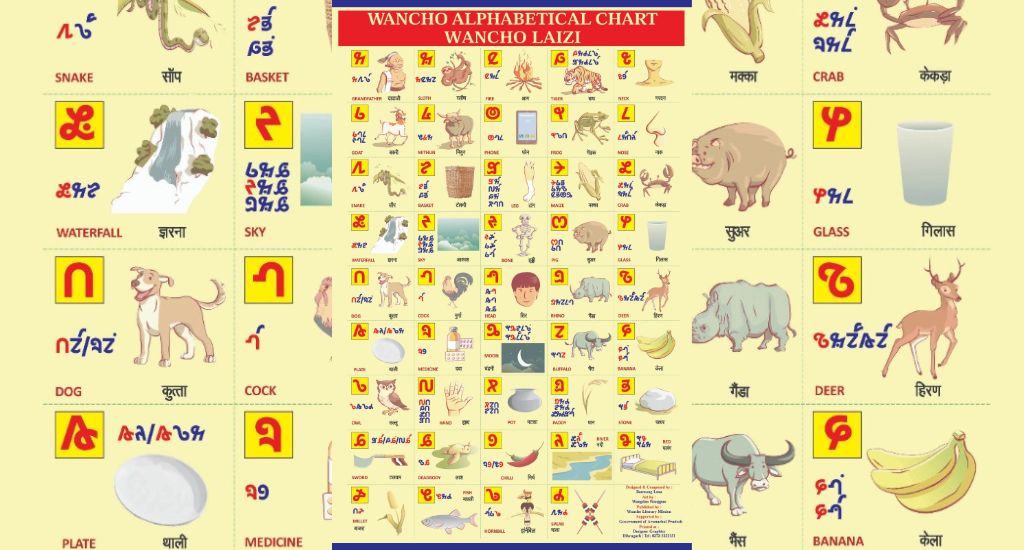

The Wancho script comprises 44 letters, with 15 vowels and 29 consonants. The letters can be combined to form 3,000 words. In 2019, the script’s Unicode application received approval.

Also Read: Present-day challenges to Adivasi languages

In the years after the COVID-19 outbreak, Losu worked to bring the script to schools. He began by developing primers, workbooks and alphabet charts to help students learn the language. Animation films were made to kindle an interest among the children in learning the script of Wancho language they converse in. The Tata Steel Foundation Samwaad Fellowship helped him develop these course materials.

Multiple rigorous workshops were held. About 200 people from the community attended the workshops to learn more about the script. The month-long workshops helped train teachers so that they could teach the children. In the first batch, 20 primary school teachers were trained to read and write Wancho script.

These trained teachers then took the script to school. It’s part of the curriculum now, and the students take classes and also appear for exams. Nearly 5,000 children across all government-run schools in the district are learning to read and write the language.

“Everybody can speak the language but not read or write it. For a language to survive, the next generation must learn the language in its entirety. There is a lot of influence from other cultures and languages, and if we do not teach the script to our children, they might eventually stop talking in the language,” said Losu.

However, now the teachers who were trained by the Wancho Literary Mission – a group dedicated to sustaining the Wancho script – await renewal of their work contract as their tenure has come to an end.

Also Read: Books in tribal languages help rejuvenate school learning in central India

“The government is printing books, but there are no teachers to teach lessons from these books in school. A new batch of teachers is yet to be trained. If the contract is not renewed for the old ones, the government won’t pay them,” said Losu.

He has been paying the teachers out of his pocket. But with the lack of a salary, he fears that the teachers will lose interest to continue teaching.

“And in the coming years, we might not have teachers anymore,” he said.

For most parents, this is an opportunity that they never had, and one that they don’t want their children to miss.

“The script is very new for us. We never learned it when we were in school. So it’s difficult for us to teach our children. It is important that the system is completely formalised, the teachers are retained and they continue to teach the language,” said a parent.

Losu also plans on printing storybooks with folktales and stories from the community that can be used as literature.

Watch: Tribal school in Bengal defies odds, nurtures cultural roots

“We have worked on the texts, but they are yet to be printed as proper textbooks. It depends on how we can sustain it in the school curriculum,” he said.

The lead image at the top shows students in a government school in Longding district with workbooks printed in the Wancho language. (Photo courtesy Banwang Losu)

Aishwarya Mohanty is an independent journalist based in Odisha. She reports on the intersection of gender, social justice, rural issues and the environment.