Villagers save in a deity’s name for rainy day

Village God’s Funds, a traditional practice of pooling money and lending to shareholders with just a social collateral, help villagers save and borrow money for emergencies

Village God’s Funds, a traditional practice of pooling money and lending to shareholders with just a social collateral, help villagers save and borrow money for emergencies

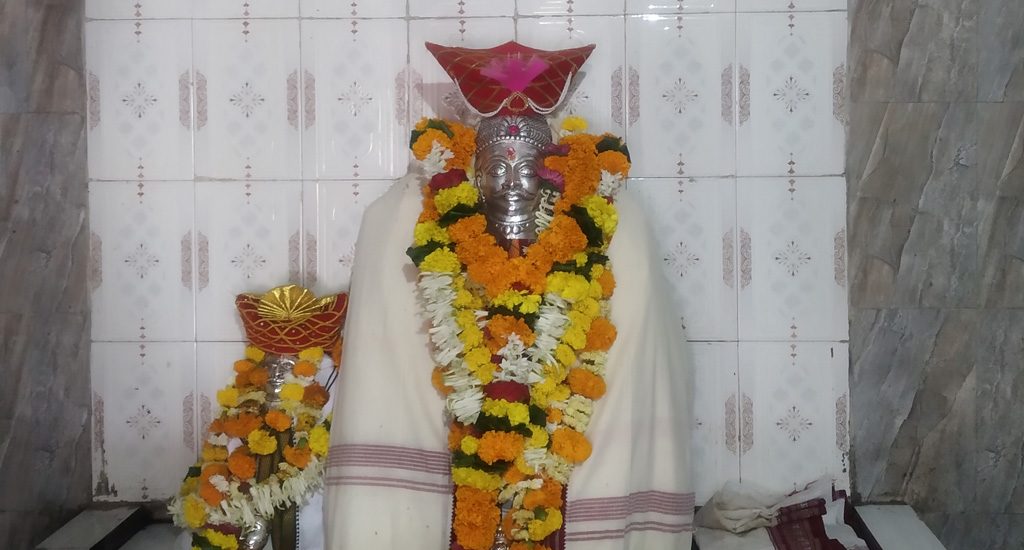

In the Maval region of Pune district in Maharashtra, mostly covering the Sahyadri mountain ranges, every village conducts a village fair in the name of the village deity. Villagers who have migrated for work, do their best to come for the festival, which is held in the beginning of a new year as per the Hindu calendar.

It is one of the special occasions when villagers invite relatives and friends. It’s a grand celebration with feasts. In the evening traditional performance arts such as Tamasha, Lavani, Bharud, Kirtan, besides live orchestra performances, and film screening are organized.

What sets this region apart from the others is the traditional saving practices followed here. During the festival, no family is apprehensive about the financial position. Because they know that they can count on the Village God’s Fund. Though the name sounds strange, it is a traditional method of saving and lending among members.

Ancient tradition

Generally called as Village God’s Fund, this practice has been going on since long time. “These village funds have been here since ages. My parents and grandparents used to be members of the village fund,” Pandurang Maragale, a villager who has just passed the age of 65, told VillageSquare.in.

In the early days, fine collected from villagers for any wrongdoing or for not following rules, and the fee collected for using village common properties were put in as the Village God’s Funds. Conflicts within the village were resolved by a committee of village elders. There was a service charge for such conflict resolution.

“Also, the money was used for common purposes such as weddings in the village and village festivals,” Mahadev Kangude, a resident of Mulashi taluk, told VillageSquare.in.

When government introduced the panchayat system, the traditional local governance method was lost. The village committee no longer functions. Nor does it give judgment on local conflicts and impose fines on wrong doers.

Many villagers said that it is unclear when exactly the Village God’s Funds transferred to the present day functioning and stopped collecting fines. But shares were invested even before the panchayati raj system was brought in.

Similarities to collectives’ funds

Somewhere along the line, the system of collecting fines changed and villagers started contributing money as an individual or as a family. These collections are pooled together, with proper records of the collections. The money is later used for various individual purposes of the members.

The process is very much similar to the way the present-day self-help groups (SHGs) function. Unlike in SHGs, Village God’s Fund has shares of the head of a family or of all family members. Instead of bank affiliation, educated and trusted elders take care of the village funds.

The meeting is held once a year when the villagers come together for the village deity’s festival. Bhairavnath, Shankar, Hanuman, Ram and Mhasoba are some of the common deities in whose names festivals are conducted. Unlike this annual meeting, SHGs conduct meeting on the weekly or monthly basis.

Pooled resources

The population in these villages vary from 300 to 1,000, where the majority practice agriculture and some work in nearby cities. The practice was initiated for saving purposes. The money is collected only when the fund is established. A person could contribute Rs 50 to Rs 1,000.

As the name indicates, the fund is established during the festival, with the money from villagers. During the village deity’s festival, the capital, i.e. the pooled money, is divided and lent to members as per their needs. When a member has to borrow money s/he will ask or nominate another person to be the social collateral. The person will be held accountable if the borrower defaulted on payment.

The interest ranges between 10% and 25%. The interest rate and the amount to be a lent to a person are mutually decided at the annual meeting. The person who borrowed the money returns the capital and the interest at the next year’s festival.

A villager explained that if he borrowed Rs 10,000, he would return Rs 12,000 at the next year’s festival, if the interest was 20%. The total amount collected after each person returns the borrowed money and interest becomes the capital for the next round of lending. The cycle goes on. Thus, the total amount of the Village God’s Funds keeps increasing every year.

Now one can observe a big village fund with 100 to 500+ shares and the fund is 10 to 25 years old. The total money can easily go up to lakhs of rupees. When the capital and the interest reach a large amount and it is quite hard to manage, the fund is broken, and the money is distributed equally among the shareholders. Then they start a new fund.

Handy resource

Members spend the borrowed money from the fund for various purposes. “I will use it to get my daughter married. The money will be used for covering the wedding related expenses, such as food and clothes,” Ramabai Bavdhane, a villager, told VillageSquare.in.

One of the reasons she chose to borrow money from the fund instead of taking a loan from the bank or the landlord is the easy availability of the fund. She does not have to show any identity card or official documents. Unlike banks where she will have to give land documents or gold as collateral, managers of the fund trust her enough to lend without collaterals.

She needs to be member of the fund to avail of the facility. Villagers see this as a good option as it is convenient and the interest they pay later would benefit everyone. Most of the villagers see this as a good opportunity to come together and share their happiness and burdens together.

Challenges

Many villagers are not educated, and the records on paper cannot be permanent. Accountability and poor management sometimes lead to the shutting down of funds. When a person and the person who signed as collateral are not able to repay, there are losses and they close it. Thus, many shareholders lose their money.

When many people come together for a collective purpose, the village politics can have an effect on the purpose and the end goal. This has at times has led to many mini funds in the same village. Though the cases are rare, people lose money in mini funds more than in the large Village God’s Fund.

“Once, a shareholder from my mini fund was not able to return Rs 20,000 that he had borrowed to set up a business. There was an issue with the records also. The person who signed as witness was also struggling financially. The borrower went bankrupt and did not even attend the village fund meetings that took place once in a year,” Ramabai Bavdhane, told VillageSquare.in.

As the prospects of getting the money from the borrower looked thin, other shareholders started protesting. “Eventually we got less money as he could not pay,” said Ramabai Bavdhane. But such cases are rare as the fund runs on trust among villagers. Cases of defaults are rare, as s/he will have a hard time winning the villagers’ trust back, given that the community is close-knit.

Opening a bank account and keeping the financial details along with official documentation can give surety. Connection with the bank can also keep the records of the money and transaction easy to track. Thus, capacity building along with conflict management skills will be useful for the smooth flow of the fund and serve the purpose to a greater extent.

Kailas Kokare is pursuing masters at Azim Premji University. He was a research intern at VikasAnvesh Foundation earlier. Views are personal.