Arecanut goes from yucky paan stains to dandy dye

Much maligned for the paan stains, betelnut juice is now being used as a natural dye by artists and the textile industry, offering a good income source for areca nut farmers of Karnataka

Much maligned for the paan stains, betelnut juice is now being used as a natural dye by artists and the textile industry, offering a good income source for areca nut farmers of Karnataka

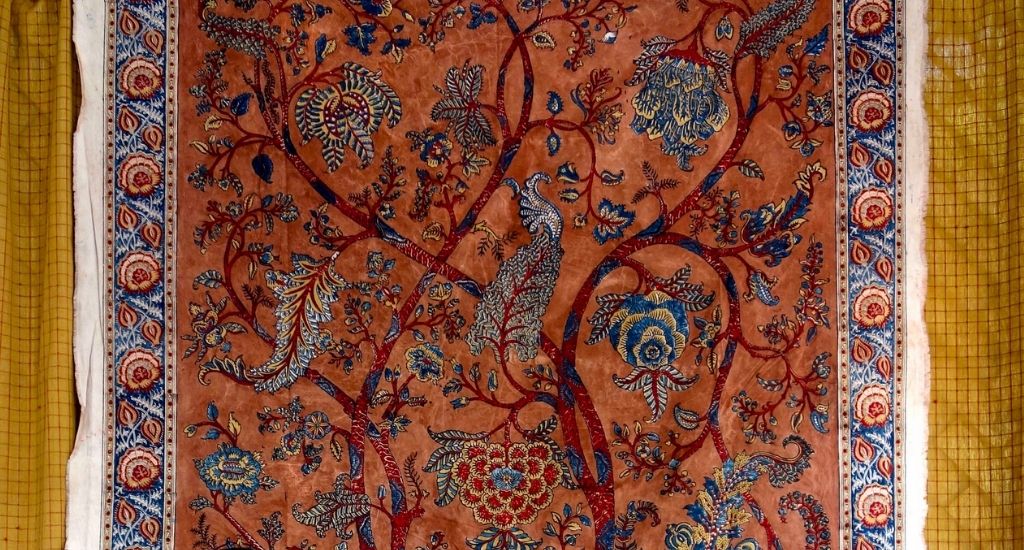

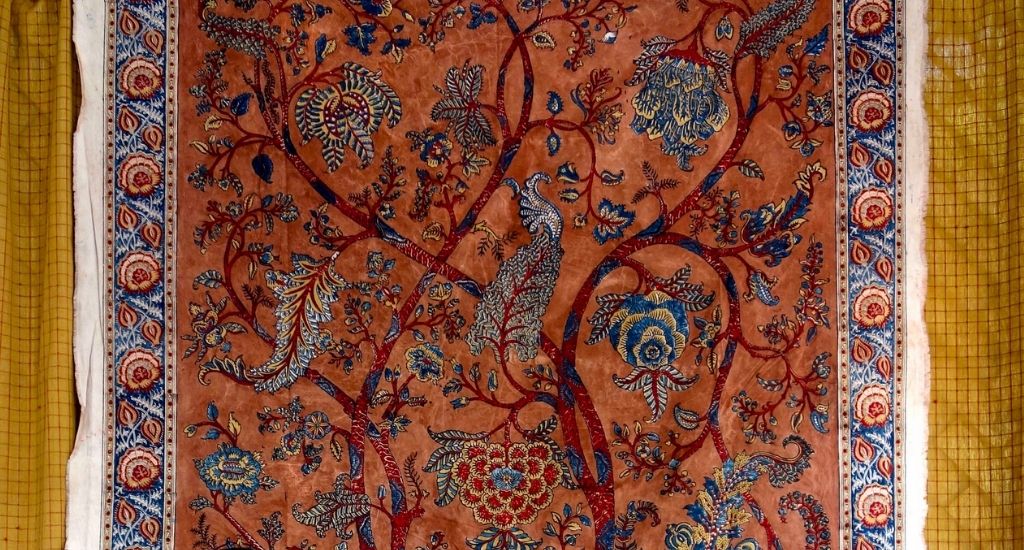

Pitchuka Srinivas’s kalamkari paintings bear no resemblance to the streaks of red splashed over sidewalks, bus stops and other public spots, unless he reveals — with great pride — the source of the ink used in his artworks.

“My Tree of Life wall hangings were much appreciated. I sold them to a client in the United States for $120 apiece. It has shades of brown, a natural dye prepared from the areca nut,” said Srinivas, who hails from Pedana at Machilipatnam in coastal Andhra Pradesh.

People chewing parcels of betel leaf wrapped around areca nut, also called betel nut, combined with slaked lime and other condiments is a ubiquitous sight in India. Aficionados often chew paan all day long, filling their mouths with betel juice and enjoying the mild high, their lips, teeth and tongue turning a dark red. The dried reddish-brown spittle is so stubborn that even the heat, dust and rain of the tropics fail to smudge those ugly specks.

But for artists and chromatographers, it’s a natural colourant worth “dyeing” for.

Srinivas always keeps an eye open for natural dyes because only organic colours are used in kalamkari, an ancient style of hand painting done on cotton or silk fabric with a tamarind pen.

Srinivas isn’t the only one. Ajrakh printers of Kutch, toymakers of Visakhapatnam, garment-makers of Shivamogga, and Kanjeevaram sari weavers of Coimbatore are using betel nut juice as a colourant.

Ramesh Ayodi, a 29-year-old weaver from Guledgudda in Karnataka recently discovered the betel dye.

“I sold three Ilkal silk saris dyed majorly in chogaru (areca nut slurry). Each sari was sold at Rs 11,000,” Ayodi said.

Jameelya Akula of Sankalpa Art Village in Visakhapatnam is equally excited about the betel dye.

“We recently used it for upcycled toys and tie-dye fabrics,” he said.

Also Read | An ancient art is earning modern dividends in Khasi Hills

But how did a stain known only for its nuisance value become a fad? Sometimes an idea is all it takes to get something going. Such was the case for scientist Dr Geeta Mahale 26 years ago when she visited Sirsi in north Karnataka, famous for its areca nut fields.

“I saw people spitting on the road. The colour caught my eye. It had rained, but the stains didn’t wash away,” said Mahale, who was then working as a senior scientist at the All India Coordinated Research Project-Clothing and Textile.

She collected samples of chogaru, and took them to her lab. She tried using it in a variety of ways: printing, painting and as a powder.

“I got vibrant shades of brown, rust and black. We also created a skin-friendly concentrate for Holi,” said Mahale, who recently retired as a professor at the University of Agricultural Sciences in Dharwad.

The Indian Council of Agricultural Research gave her an award in 2001 for her pioneering research.

Humanity has been making dye from plants since the time of the cave-dwellers. Such dyes are eco-friendly as they come from natural sources.

Hibiscus gives a beautiful purple dye. Roses and lavender bring out a brilliant pink hue. Marigolds and sunflowers produce shades of yellow, as does turmeric. Manjistha or Indian madder is used to get red, pink and orange dyes. The other natural sources of dyes are gal or Aleppo oak for ivory, light yellow and grey; lac for red and violet; mulberry for green; pomegranate for red, yellow, khaki and grey; indigo for deep blue; and katha or catechu for brown. The extract of acacia trees is used as a food colour, astringent, tannin, and dye. Chogaru has the potential to replace catechu which is a forest produce.

Also Read | Go gypsy this summer with colourful Lambani decor

The betel nut slurry crystallises under the sun and gives off a warm, bold, earthy tone — a shade of brown with a tinge of red.

The spicy date-like fruit of the areca palm is processed into hardened supari for paan and gutkha by soaking the raw kernels in water and boiling them for hours. These are then sundried. What’s left of the water is the thick slurry, called chogaru in Karnakata.

It’s a good time to put this stain in the game as the natural dye market is growing big. That’s good news for Venkataramana Bhat, a 50-year-old farmer from Vanalli village in Sirsi. He processes around 15,000 litres of betel slurry annually, buying his supplies from fellow farmers at Rs 10 a litre.

“It becomes thick as honey after a fortnight of drying in the sun. We sell it to traders for Rs 80 a litre,” Bhat said.

Karnataka is the top producer in India of betel nut, with an acreage of 5.49 lakh hectares. Chikkamagaluru district leads in areca palm cultivation, followed by Shivamogga and Davangere districts. In 2020, the state produced 77 percent of the country’s total yield.

Charaka, a women’s cooperative in Karnataka’s Shivamogga, is among the earliest users of chogaru. It produces naturally-dyed cotton garments, which are sold under the brand name of Desi.

“We produce about 30,000 metres of fabric each month, of which 12,000 metres are dyed using areca nut slurry,” said Terence Peter, an administrator of Charaka.

It’s not a rosy picture throughout though. Shree Padre, the editor of Kannada farm monthly Adike Patrike, said that the unorganised nature of the business poses problems.

“The challenge is to stop the slurry from wasting. Farmers typically discard huge quantities of it because most of them are unaware of its real worth,” Padre said.

Also Read | Kokum fruit juice tastes of success in Karnataka

The lead image at the top shows the ‘Tree of Life’ motif prepared by Pitchuka Srinivas in Kalamkari art style using areca nut dye (Photo by Adike Patrike)

Hiren Kumar Bose is a journalist based in Thane, Maharashtra. He doubles as a weekend farmer.